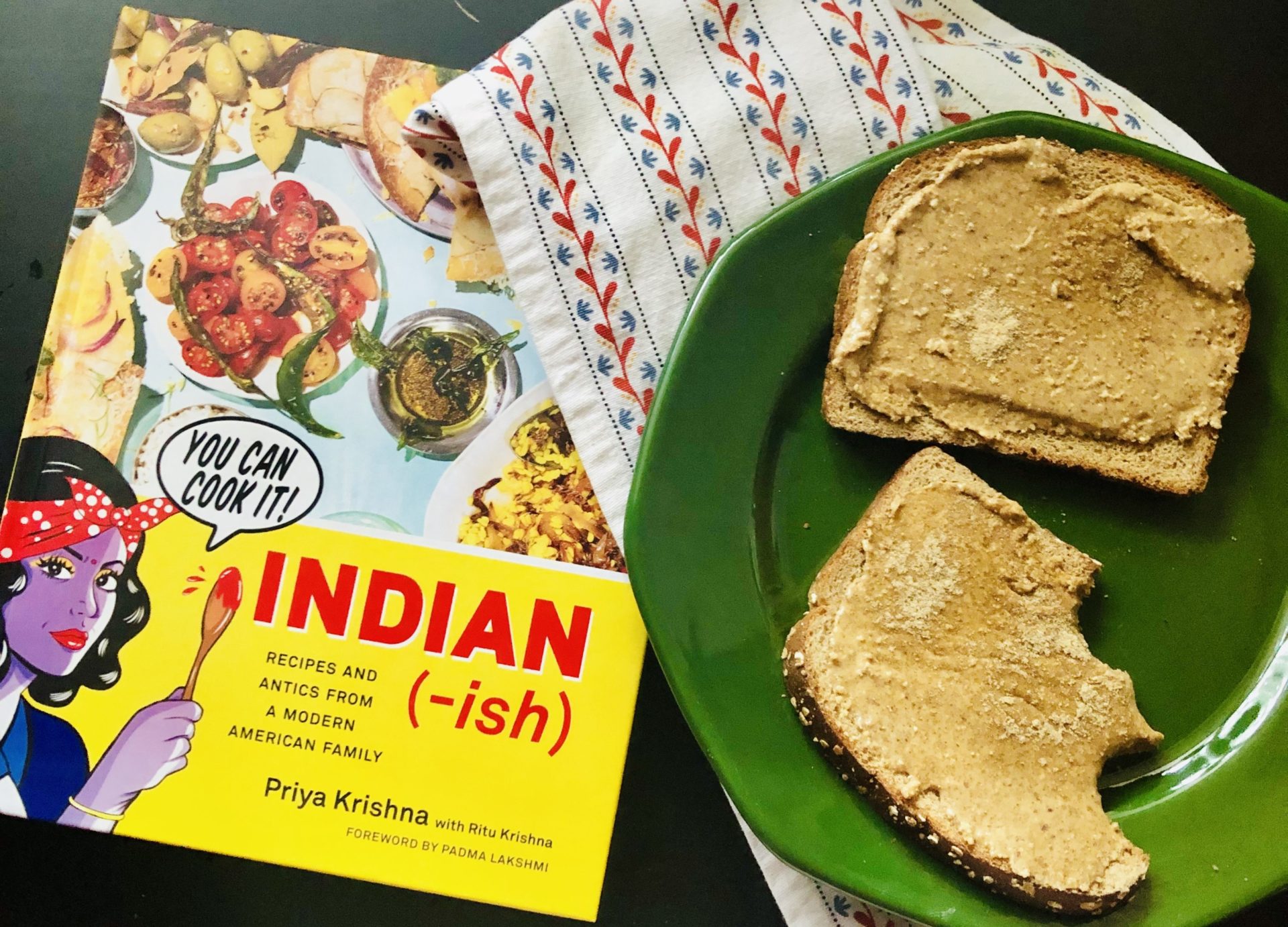

Pictured above: Reading Indian-ish with a side of Chaat Masala Almond Butter Toast

Join us in celebrating Asian American/Pacific Islander Heritage Month! We’re highlighting AAPI literature and members of our state’s literary community—starting with our own Logistics and Volunteer Coordinator, Nicole! Here, she explores her love of cookbooks and food writing, as well as the vital connection between food and cooking and her cultural identity.

**

Growing up, it always felt as if, while I was both Asian and American, I somehow didn’t fit either of those categories. Considering myself more Asian would garner strange looks at my clearly half-Caucasian facial features, yet growing up so little in America meant friends often ate dinner at home prior to sleepovers at my house for fear that we would serve them Fish Head Curry (which we never did). But I always connected with the cultural identity of Singapore because that was all about food. Singapore itself is a big melting pot of people and cultures, and the great connector has always been food. Being half Singaporean meant I grew up with an opinion on everything related to food, and knowing I could at least relate to other people through that, because everyone needs to eat.

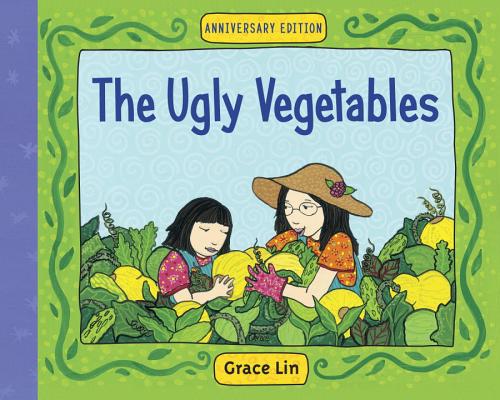

I started cooking with my mom from a very early age, learning firsthand on how to create passed down recipes. Shopping for ingredients with my mom always felt special. When we were still living in Singapore, it meant going to open air markets. We would talk to the passionate vendors and haggle about the prices—a direct connection to the farms and farmers. I read The Ugly Vegetables by Grace Lin with my cousin not too long ago and it reminded me of those interactions. The Ugly Vegetables is a children’s picture book about a child frustrated that her mother won’t plant pretty flowers, only ugly vegetables, until she realizes those vegetables make the most delicious Chinese vegetable soup. I knew walking into those markets that whatever we ended up buying, even if it smelled funny or looked unusual, would be turned into something delicious in the end.

I started cooking with my mom from a very early age, learning firsthand on how to create passed down recipes. Shopping for ingredients with my mom always felt special. When we were still living in Singapore, it meant going to open air markets. We would talk to the passionate vendors and haggle about the prices—a direct connection to the farms and farmers. I read The Ugly Vegetables by Grace Lin with my cousin not too long ago and it reminded me of those interactions. The Ugly Vegetables is a children’s picture book about a child frustrated that her mother won’t plant pretty flowers, only ugly vegetables, until she realizes those vegetables make the most delicious Chinese vegetable soup. I knew walking into those markets that whatever we ended up buying, even if it smelled funny or looked unusual, would be turned into something delicious in the end.

My mom’s recipes always consisted off “a bit of this” or “a splash of that,” and eventually we would get to the “and now let the flavors sit and talk to one another” step. I didn’t know how important those recipes would be until I lived on my own and began to miss those flavors. When I visit my mom now, I’ll ask her to make a dish and then hover around her with a notepad, trying to create a set of cooking steps. I write out these recipes knowing that if I wasn’t willing to take the time to do this, the delicious dishes she’s created over the years would be lost forever.

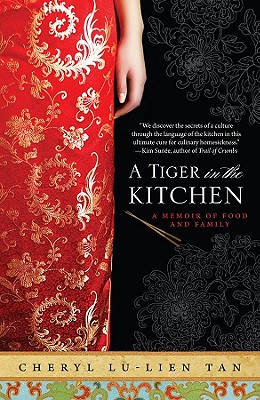

I remember distinctly having déjà vu when I started to read A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan. While Tan was writing about her own experiences surrounding learning family traditions to create delicious food, it felt like she was writing about my own. Tan is also from Singapore and writes about the same food-obsessed city and culture, yet it still felt like something I had never read about, only experienced firsthand. Reading her book was one of the first times I felt “seen,” like someone else understood the complexities of getting a recipe from your auntie when she hasn’t ever written the recipe down.

I remember distinctly having déjà vu when I started to read A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan. While Tan was writing about her own experiences surrounding learning family traditions to create delicious food, it felt like she was writing about my own. Tan is also from Singapore and writes about the same food-obsessed city and culture, yet it still felt like something I had never read about, only experienced firsthand. Reading her book was one of the first times I felt “seen,” like someone else understood the complexities of getting a recipe from your auntie when she hasn’t ever written the recipe down.

My mom’s recipes range from very traditional dishes like beef rendang or sambal goreng to hand-tailored dishes from my childhood, where she would throw fried hot dogs into her fried rice to get my brother and me to eat leftovers. It was very clear that she cared for us through how she cooked, that preparing us food was the equivalent of her saying, “for whatever you are celebrating or going through, I’m here.” Connection with food is important for so many cultures because it somehow signals a level of openness, an invitation to celebrate the other’s cultures through taste. This is why I read cookbooks like novels: each recipe tells a story about the creator and their relationship to food and culture.

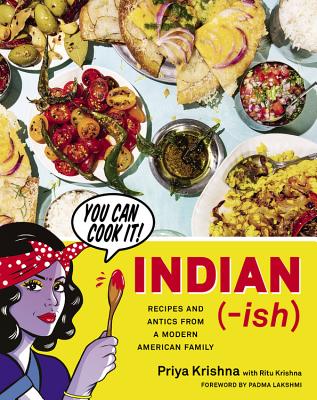

I’ve recently started Indian-ish: Recipes and Antics from a Modern American Family by Priya Krishna, and it’s been a real treat to read recipes that are a lot like my mom’s. While the recipes are still rooted in the Indian culture, author Priya Krishna lets you in on her specific family’s recipes, her versions of hot dog fried rice. She makes Malaysian noodles with a ramen packet and her Shahi Toast is actually an aromatic bread pudding. The simplest addition of chaat masala spice to almond butter toast feels like her personal comfort food, a part of her past and her present merged on a piece of toast.

I’ve recently started Indian-ish: Recipes and Antics from a Modern American Family by Priya Krishna, and it’s been a real treat to read recipes that are a lot like my mom’s. While the recipes are still rooted in the Indian culture, author Priya Krishna lets you in on her specific family’s recipes, her versions of hot dog fried rice. She makes Malaysian noodles with a ramen packet and her Shahi Toast is actually an aromatic bread pudding. The simplest addition of chaat masala spice to almond butter toast feels like her personal comfort food, a part of her past and her present merged on a piece of toast.

This type of marriage of food cultures really speaks to me, an unexpected reflection of myself in food. It always was hard to understand myself based on labels, but I’ve been learning about myself based on my taste in food. When you’re able to figure out your tastes and what you find personally interesting, it tells you more about who you are as a person. For me, a Singaporean-American who particularly likes fried meats and aromatic spices, that’s something I can identify with.